Make it George Bellows.

Like athletes? He paints ’em. Like seascapes? Yeap, does that too. Religious paintings? Why not. What about rough and tumble street life? He’s a pro.

Forget Matisse: In Search of True Painting. It’s a flat-liner. I know, I know, you love Matisse, and of course you do. Matisse is a blue-chip crowd-pleaser, but the assemblage of paintings reveal nothing new nor nothing unique to Matisse. It is, effectively, thoroughly expected. He painted the same subject over and over. His style changed. He reworked paintings. It has the feeling of a student exhibition — here’s a thesis and here are all the paintings in our collection (plus a few on loan from friends) that support it.

Instead, wander up to the second floor, where George Bellows waits to knock your socks off.

Once again, Dr. H. Barbara Weinberg struts her stuff as the most formidable curator in Pre-1945 American Art. Well paced and smartly edited, the exhibition is the first comprehensive retrospective on Bellows in half a century. On display is his artistic range, revealing subjects in his oeuvre often subsumed to his find-them-in-every-textbook painting of boxers caught mid-bout.

George Bellows (1882-1925) died of appendicitis when he was only 42. His career and life were short, his artistic achievement, almost immeasurable.

He is best known as a core member of the Ashcan School — a group of New York painters, mostly students and associates of Robert Henri, whose style and subject matter confronted both the academy and American Impressionism. They were urban realists who painted gritty street scenes of the New York City’s working class, the city’s modernizing landscape, current events, and portraits with dark palettes and expressive brush work. Rather than art for art’s sake, they worked by Henri’s creed: “art for life’s sake.”

Bellows is the most recognizable of the Ashcan School, and his paintings are usually invoked as representative of their overall style. If you’ve picked up a textbook on American Art, his paintings and lithographs of boxers and the development of Pennsylvania Station get prime billing.

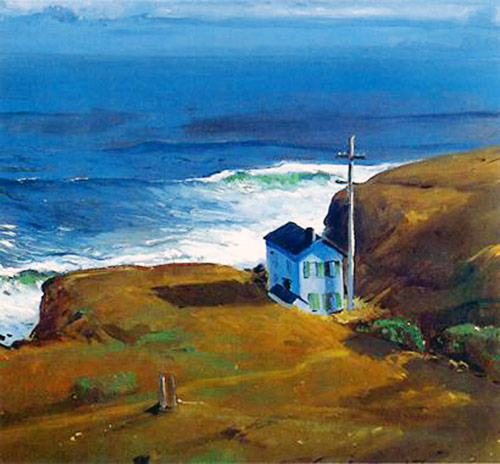

What you don’t typically see are his landscapes, his seascapes of Camden, Maine, his moonlight scenes of Riverside Park, or his religious allegories. The exhibition begins by introducing us to Bellows through what we know best and using his education at Ohio State University and talents as an athlete (legend goes he could have gone pro) as context for the subject that would later become his historical calling card.

And then you turn the corner to learn something new, see something unexpected. The first vista onto every new gallery is a view onto another showstopper, but also another a look into another chapter of Bellow’s career.

It’s the kind of exhibit that demands a long linger, as it reveals as much about a particular period in New York City’s history as it does about a canonized artist and the art world he negotiated.